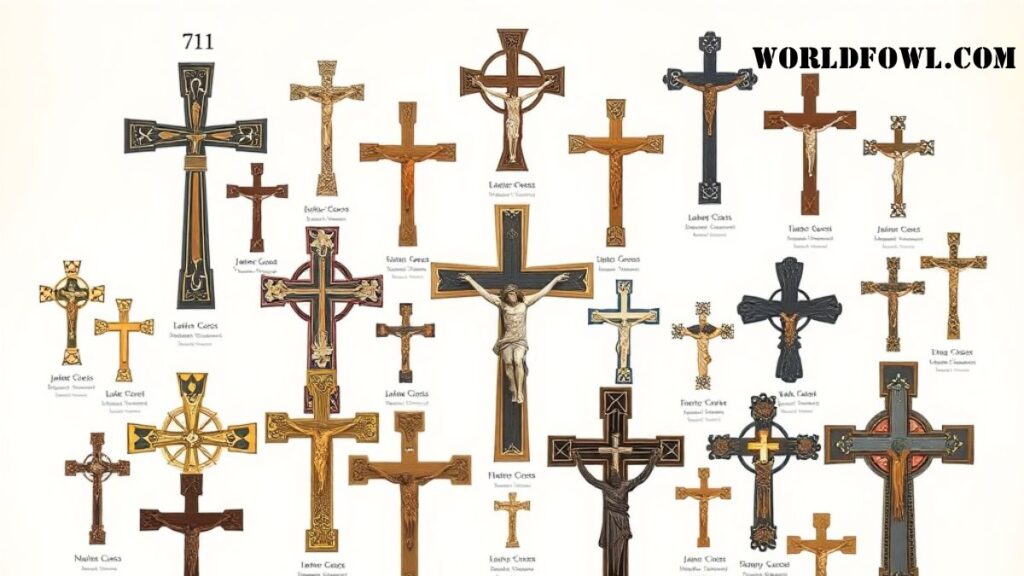

71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained The types of Christian crosses encompass over 71 distinct variations, each representing unique theological meanings, historical contexts, and cultural expressions of faith. From the universally recognized Latin cross to the ornate Ethiopian cross, these sacred symbols chronicle Christianity’s two-thousand-year journey across continents.71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained Understanding the history of crosses reveals how believers adapted this central emblem to reflect regional artistry, denominational theology, and spiritual devotion.

Picture a medieval knight bearing a red Templar cross into battle, an Orthodox priest blessing worshippers with an elaborate Ethiopian cross, or Irish monks carving intricate Celtic crosses into towering stone monuments.71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained Each cross tells a compelling story of martyrdom, salvation, and cultural identity that transcends mere religious symbolism.

71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained This comprehensive exploration unveils the meanings of crosses ranging from apostolic era symbols like the Chi-Rho to heraldic crosses of medieval chivalric orders. You’ll discover why St. Peter’s cross appears inverted, what the Jerusalem cross’s five elements represent, and how regional crosses emerged across Africa, Europe, and Asia. These sacred designs reveal Christianity’s remarkable ability to unite diverse cultures under one transformative message of redemption.

Foundation Crosses – The Original Three

Latin Cross (Crux Immissa) ✝

The Latin cross represents Christianity’s most universal symbol. Its vertical beam extends significantly below the horizontal crossbar, creating the distinctive silhouette recognized worldwide.

71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained Historical records trace this design to the 4th century, though the actual crucifixion device likely resembled this form. The proportions typically follow a 2:1 or 3:2 ratio, with the lower section longest.

Theological symbolism runs deep here. The extended lower beam points earthward, representing Christ’s descent to humanity. The crossbar signifies the bridge between God and man through sacrifice.

You’ll find this cross in virtually every Christian denomination. Catholic churches display it prominently. Protestant congregations favor its simplicity. Even secular culture recognizes its meaning instantly.

Architecture incorporates the Latin cross into church floor plans. Flying over European cities reveals cathedral layouts shaped like this cross, a practice dating to medieval times.

Greek Cross +

Four equal arms characterize the Greek cross. Each section measures identically, creating perfect symmetry.

Byzantine architecture popularized this design between the 4th and 15th centuries. Orthodox churches particularly embraced its balanced geometry.

The symbolism speaks to universality. Four equal arms represent:

- The four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John)

- Cardinal directions (north, south, east, west)

- Christ’s message spreading to earth’s corners

- Balance between divine and human natures

The International Red Cross adopted a red Greek cross on white background in 1863. This humanitarian choice carried no religious intent, though Christian symbolism influenced the selection.

Eastern Orthodox churches incorporate this cross into iconography and architectural elements. The famous Hagia Sophia in Istanbul showcases numerous Greek cross motifs throughout its structure.

Russian Orthodox Cross (☦︎)

Three horizontal bars distinguish the Orthodox cross from Western designs. This variation carries profound theological meaning within Slavic Christianity.

71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained The top bar represents the titulus—the mocking inscription “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” (INRI). The middle bar marks where Christ’s hands were nailed. The bottom slanted footrest holds special significance.

That angled lower bar tells a powerful story. Tradition holds it tilted upward toward the penitent thief who asked Jesus to remember him in paradise. The downward side points toward the unrepentant thief who mocked Christ.

Russian Orthodox churches display this cross prominently. You’ll spot it atop domes throughout Eastern Europe and Russia.

The design survived Soviet persecution remarkably. Despite communist attempts to eradicate religious symbols, believers secretly preserved these crosses. Many families buried them, later retrieving them after 1991.

Early Christian & Apostolic Era Crosses

Chi-Rho (Labarum) ☧

Emperor Constantine saw this symbol before the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 AD. The vision changed history.

Two Greek letters overlap here: Chi (Χ) and Rho (Ρ)—the first letters of “Christos.” Constantine ordered his soldiers to paint this Christian symbol on their shields.

They won decisively. Christianity shifted from persecuted sect to imperial religion.

Archaeological excavations in Roman catacombs reveal Chi-Rho symbols dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries. Early Christians used it as coded identification during persecution periods.

Modern liturgical contexts still employ this ancient symbol. Papal vestments, altar cloths, and ecclesiastical banners feature the Chi-Rho regularly.

Staurogram ⳨

The Staurogram represents Christianity’s earliest cross symbol. Second-century papyri contain this tau-rho ligature, predating full cross depictions by decades.

Scholars discovered it in the Bodmer Papyri, dating to roughly 200 AD. These manuscripts show early Christians abbreviating “cross” (stauros in Greek) with this combined symbol.

Why use abbreviation? Religious persecution made overt Christian identification dangerous. The Staurogram functioned as subtle recognition among believers.

The overlapped tau (Τ) and rho (Ρ) create a figure resembling a person on a cross—remarkably symbolic for such an early design.

Ankh Cross (Crux Ansata) ☥

The Egyptian ankh cross sparked theological debates for centuries. This ancient hieroglyph meaning “life” predates Christianity by millennia.

Coptic Christians in Egypt adopted the ankh, merging it with crucifixion imagery. The loop represents eternal life through Christ’s resurrection.

Critics argue this constitutes syncretism—blending pagan symbols with Christian theology. Defenders counter that redeeming cultural symbols demonstrates Christianity’s transformative power.

Archaeological evidence from 4th-century Coptic Egypt shows frequent ankh usage. Textile fragments, pottery, and tomb inscriptions feature modified ankh designs resembling traditional crosses.

Modern neo-pagan movements appropriated the ankh, complicating its Christian associations. Jewelry featuring ankhs often carries ambiguous spiritual meaning today.

Tau Cross (St. Anthony’s Cross)

The T-shaped Tau cross connects directly to Old Testament prophecy. Numbers 21:8-9 describes Moses lifting a bronze serpent on a pole—interpreted as Christ’s crucifixion prefigurement.

St. Francis of Assisi adopted this cross as his personal signature. Franciscan friars wear it prominently, honoring their founder’s devotion.

Medieval pilgrimage routes featured Tau cross markers. The Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony used it extensively, earning the designation “St. Anthony’s Cross.”

The simple T-shape carries profound symbolism. It represents:

- The crossbar of Christ’s burden

- The prophetic bronze serpent

- Humility and simplicity

- Franciscan poverty vows

Don’t confuse it with the Egyptian ankh. While visually similar, theological meanings differ substantially.

Anchor Cross (Mariner’s Cross)

Hebrews 6:19 calls hope “an anchor for the soul, firm and secure.” Early Christians seized this metaphor.

Roman catacomb frescoes depict anchors with crossbars shaped like crosses. Persecution-era believers disguised their faith through maritime imagery.

Sailors embraced this symbolism naturally. Naval chaplains and maritime Christian communities adopted the anchor cross as their distinctive emblem.

The design cleverly combines practical nautical imagery with profound spiritual truth. An anchor provides stability during storms—precisely what Christ offers believers.

Modern grave markers in coastal regions frequently feature anchor crosses, particularly for deceased mariners or Navy veterans.

Golgotha Cross (Calvary Cross)

Three steps form the base of the Golgotha cross. Each level holds symbolic meaning.

Mount Calvary, called “Golgotha” (Place of the Skull), stood outside Jerusalem’s walls. Crucifixion occurred on this elevated ground.

The three-stepped platform represents:

- Faith, hope, and charity

- Body, soul, and spirit

- The Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit)

Crusader architecture prominently featured this design. Knights returning from the Holy Land incorporated Calvary crosses into European church construction.

Eastern and Western Christianity developed distinct variations. Orthodox versions typically appear more ornate, with elaborate metalwork. Western designs favor simpler stone construction.

Liturgical furnishings often incorporate this cross. Altar designs, processional crosses, and architectural elements frequently display the characteristic stepped base.

Papal, Ecclesiastical & Hierarchical Crosses

Papal Cross (Triple Cross)

Three horizontal bars declare papal authority. The Papal cross appears exclusively in contexts involving the Pope.

Historical development traced Byzantine imperial insignia. Early popes adapted imperial Roman symbolism to assert spiritual authority matching temporal power.

The three bars symbolize:

- Pope’s authority over church, heaven, and earth

- Triple crown (tiara) correspondence

- Teaching, sanctifying, and governing roles

Papal processions feature this cross carried before the pontiff. Vatican ceremonies maintain strict protocols regarding its display.

Distinguish this from the Patriarchal cross (two bars). Cardinals and archbishops use two-barred crosses, never three.

Crucifix (Corpus Cross)

A crucifix displays Christ’s body (corpus) on the cross. This distinction separates Catholic tradition from Protestant practice.

Catholic Church theology emphasizes Christ’s suffering. The corpus serves as perpetual reminder of sacrifice for salvation.

Protestant reformers rejected crucifixes generally. They argued empty crosses better symbolize resurrection victory over death.

Medieval craftsmanship created increasingly realistic corpus figures. The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald depicts Christ’s agony with disturbing accuracy—intended to comfort plague victims.

San Damiano Cross influenced St. Francis profoundly. This Byzantine-style painted crucifix spoke to him, commissioning his mission to “repair my church.”

Contemporary debates continue regarding artistic representation. Traditional realistic depictions compete with modern abstract interpretations.

Marian Cross

The stylized “M” merged with a Latin cross honors the Virgin Mary. This relatively modern design gained popularity through 19th-century Marian apparitions.

The Miraculous Medal vision experienced by St. Catherine Labouré featured this symbolism. Subsequent devotion to Mary’s Immaculate Heart spread the design globally.

Marian Cross jewelry became common among Catholic faithful. First Communion gifts frequently include necklaces featuring this symbol.

Apparition sites like Lourdes, Fatima, and Medjugorje prominently display Marian crosses. Pilgrims associate it with Mary’s maternal intercession.

Theological significance centers on Mary’s role in redemption. She stood at the cross’s foot (John 19:25), uniting her suffering with Christ’s sacrifice.

Regional & Cultural Cross Variations

Celtic Cross

A distinctive circle (nimbus) surrounds the Celtic cross intersection. This iconic design defines Irish and Scottish Christian art.

Theories about the circle’s origin spark debate. Did it represent:

- Pre-Christian sun worship elements?

- Halo indicating Christ’s divinity?

- Structural support for stone monuments?

- Eternity’s endless nature?

High crosses throughout Ireland showcase intricate knotwork. The Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice dates to 923 AD, standing over 18 feet tall.

Celtic Christianity developed unique characteristics partly due to geographical isolation. Roman liturgical practices arrived later, allowing indigenous traditions to flourish.

Modern Celtic cross revival connects to Irish cultural identity. Diaspora communities worldwide display these crosses as heritage markers.

White supremacist groups unfortunately appropriated Celtic crosses in recent decades. This misuse distorts the symbol’s authentic Christian heritage.

Jerusalem Cross (Crusader’s Cross)

Five crosses compose the Jerusalem cross—one large central cross surrounded by four smaller ones. Each element carries meaning.

The five crosses represent:

- Christ’s five wounds (hands, feet, side)

- Gospel spread to earth’s four corners

- Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Five books of the Pentateuch

Crusades-era Latin Kingdom (1099-1291) adopted this as their official emblem. Knights tattooed it, wore it on surcoats, and flew it from castle walls.

Modern Israel’s Christian communities maintain strong attachment to this symbol. The Custody of the Holy Land Franciscans use it extensively.

Christian Zionist movements sometimes appropriate the Jerusalem cross, creating controversy. Political implications complicate its religious significance.

Ethiopian Cross

Elaborate filigree metalwork distinguishes Ethiopian crosses. No two appear identical—each artisan creates unique designs.

Coptic Christianity reached Ethiopia during the 4th century. King Ezana of Axum converted around 330 AD, establishing one of Christianity’s oldest continuous traditions.

Hand crosses serve liturgical functions during Orthodox services. Priests bless congregants by touching foreheads with these ornate crosses.

Lalibela’s rock-hewn churches (12th-13th centuries) feature Ethiopian cross motifs throughout their architecture. UNESCO designated these structures World Heritage Sites.

Ge’ez inscriptions often accompany cross designs. This ancient Semitic language preserves biblical texts and liturgical prayers.

Genocide memorials incorporate Ethiopian crosses, honoring victims of Italian fascist occupation (1935-1941) and subsequent conflicts.

Armenian Cross (Khachkar)

Stone-carved memorial crosses called “khachkars” blanket Armenia’s landscape. Over 50,000 examples survive, some dating to the 9th century.

Intricate patterns combine floral, geometric, and biblical motifs. Master craftsmen spent months creating single khachkars.

UNESCO recognized khachkar symbolism and craftsmanship as Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2010. The art form represents Armenian cultural survival.

Armenian Genocide (1915-1923) memorials worldwide feature khachkar designs. The symbol connects diaspora communities to ancestral homeland.

Liturgical usage includes blessing ceremonies at khachkar sites. Armenians visit these crosses seeking intercession and spiritual renewal.

Modern Armenia continues traditional khachkar creation. Young artisans learn ancient techniques, ensuring cultural continuity.

Maltese Cross ✠

Eight points characterize the Maltese cross. Knights Hospitaller (later Knights of Malta) adopted this distinctive emblem during the Crusades.

Each point represents a Beatitude from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:3-10):

- Blessed are people whose income is below the poverty threshold in spirit

- Blessed are they who mourn

- Blessed are the meek

- Blessed are they who hunger for righteousness

- Blessed are the merciful

- Blessed are the pure in heart

- Blessed are the peacemakers

- Blessed are they who are persecuted

The Amalfi Republic’s maritime traditions influenced the design. Sailors from this Italian city-state served as Hospitallers’ naval force.

Firefighter emblems adopted the Maltese cross during the 19th century. The connection honors Knights Hospitaller who fought fires threatening civilians during Crusades.

Modern Malta’s sovereignty incorporates this cross into the national flag and coat of arms. It symbolizes both Christian heritage and national identity.

Huguenot Cross

French Protestant refugees created the Huguenot cross during persecution periods. Its distinctive design features a dove descending between fleur-de-lis terminals.

The dove represents the Holy Spirit—comfort during suffering. Fleur-de-lis terminals maintained French cultural identity despite exile.

Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) triggered massive Protestant emigration. Hundreds of thousands of Huguenots fled France, carrying this cross as identity marker.

Diaspora communities in South Africa, America, Germany, and Britain preserved Huguenot crosses. Descendant associations still use it ceremonially.

Modern French Reformed churches display this symbol prominently. It commemorates ancestors’ martyrdom and steadfast faith under persecution.

Saint-Associated Crosses

St. Peter’s Cross (Inverted Cross)

The upside-down cross honors St. Peter’s martyrdom. Tradition holds he requested crucifixion head-downward, deeming himself unworthy to die like Christ.

Papal apartments in the Vatican feature this symbol authentically. The Chair of St. Peter displays an inverted cross, affirming papal succession.

Satanic appropriation completely distorted this Christian symbol’s meaning. Horror films and occult imagery misuse St. Peter’s cross, inverting its humility message.

Medieval art frequently depicted Peter’s crucifixion scene. The inverted position emphasized his profound humility and unworthiness before Christ.

Modern Catholics defend this symbol’s authentic meaning. Educational efforts combat widespread misunderstanding perpetuated by popular culture.

St. Andrew’s Cross (Saltire) ☓

The X-shaped cross marks St. Andrew’s martyrdom. Scotland’s flag displays this distinctive saltire design—a white X on blue background.

Tradition places Andrew’s crucifixion in Patras, Greece, around 60 AD. He supposedly preached from the cross for two days before dying.

Apostolic mission legends claim Andrew evangelized Scythia (modern Ukraine/Russia). Orthodox churches in Eastern Europe particularly venerate him.

Confederate flag misuse created negative associations with St. Andrew’s cross. This political appropriation distorts the symbol’s religious significance.

Scotland’s national identity centers on St. Andrew. His feast day (November 30) serves as unofficial national holiday.

St. Thomas Cross (Nasrani Cross)

South Indian Christians use this distinctive cross featuring a dove descending toward a lotus. The St. Thomas cross represents ancient Christian communities in Kerala.

Apostolic tradition claims Thomas evangelized India after Pentecost, establishing churches along the Malabar Coast. Archaeological evidence supports Christian presence by 2nd century.

Syrian liturgical heritage shaped these communities. Nasrani Christians maintained Syriac language in worship until recent decades.

The lotus symbolizes Indian cultural context. Unlike European lilies, the lotus resonated with local converts’ agricultural experience.

Dove imagery emphasizes Holy Spirit’s role in salvation. Combined elements create uniquely Indian Christian expression.

San Damiano Cross

This Byzantine-style painted crucifix transformed Francis of Assisi’s life. While praying before it in 1205, he heard Christ’s voice commanding “Repair my church.”

The original hangs in St. Clare’s Basilica, Assisi. Reproductions worldwide make it among Christianity’s most recognized crucifix images.

The painting depicts Christ’s resurrection through stylized artistic conventions. Unlike Western suffering emphasis, this crucifix shows Christ’s eyes open, suggesting victory over death.

Franciscan spirituality centers on this cross’s message. Friars meditate on it, finding inspiration for their mission of spiritual renewal and poverty.

Modern pilgrimages to Assisi inevitably include viewing this sacred image. The chapel where Francis heard Christ’s voice attracts thousands annually.

Heraldic & Chivalric Crosses

Templar Cross (Red Cross Pattée)

Knights Templar wore red cross pattée on white mantles during the Crusades. This military order protected Christian pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem.

The flared arms widening toward ends created distinctive appearance. Templar identification became synonymous with this design.

Pope Clement V suppressed the Templars in 1312, spurring centuries of conspiracy theories. Modern fiction wildly exaggerates their historical role.

Neo-Templar organizations inappropriately claim connection to medieval knights. Genuine historical research reveals complex financial and military operations, not mystical secrets.

Portugal’s Order of Christ succeeded Templars, adopting modified cross designs. Prince Henry the Navigator’s ships flew Order of Christ crosses during Age of Discovery.

Cross Pattée

The flared-arm cross pattée influenced numerous military and chivalric orders. German Iron Cross military decoration derived from this heraldic form.

Teutonic Knights used cross pattée variations during Baltic Crusades. Their militant Christianity spread through conquest and conversion.

WWI and WWII German military decorations continued Iron Cross traditions. Historical associations create contemporary controversy when displayed.

Heraldic precision demands specific terminology. The pattée designation indicates exact arm-widening proportions distinguishing it from similar forms.

Medieval shield designs incorporated crosses pattée extensively. Noble families displayed them as charges indicating Crusades participation.

Cross of Calatrava

Spanish Reconquista military orders adopted distinctive cross designs. The Cross of Calatrava features red fleur-de-lis terminals extending from each arm.

Founded in 1158, the Order of Calatrava defended Castilian territories from Moorish forces. Their military-monastic lifestyle combined martial skill with religious vows.

Mariana Islands flag incorporates this cross, reflecting Spanish colonial heritage. The design persists in modern heraldry centuries after Spain’s empire declined.

Modern Spanish honors system includes Order of Calatrava membership. Recipients display the cross as recognition of distinguished service.

Heraldic crosses like Calatrava’s demonstrate how religious symbolism merged with political-military identity during medieval Christianity’s expansion.

Specialized Theological & Liturgical Crosses

Resurrection Cross (Triumphant Cross)

A banner or flag attached to the cross symbolizes victory. Christ’s resurrection conquered death, transforming the crucifixion instrument into triumph symbol.

Easter liturgy prominently features resurrection crosses. Processional banners display this design, celebrating Christianity’s central doctrine.

The Lamb of God (Agnus Dei) often appears with resurrection banner. Combined imagery emphasizes Christ as sacrificial lamb achieving victory.

Byzantine iconographic tradition extensively uses triumphant cross imagery. Gold backgrounds and elaborate decoration emphasize glory over suffering.

Western medieval art balanced suffering and triumph representations. Passion narrative focused on agony; Easter emphasized victorious resurrection.

Passion Cross (Cross with Instruments)

The Passion cross displays crucifixion instruments surrounding the central form. Crown of thorns, nails, spear, sponge, and whip appear prominently.

Via Dolorosa devotional practices inspired these detailed representations. Medieval Catholics meditated on each suffering stage systematically.

Late medieval piety emphasized Christ’s agony increasingly. Black Death’s horror drove believers toward contemplating Christ’s comparable suffering.

Sorrowful Mysteries rosary meditation connects to Passion cross imagery. Catholics pray through Christ’s suffering as spiritual exercise.

Devotional art featuring passion instruments declined post-Reformation. Protestant theology deemphasized suffering contemplation favoring resurrection focus.

Tree of Life Cross

Branches sprout from this cross design, merging Eden’s tree with Calvary’s wood. Genesis and Revelation imagery converge powerfully.

Redemption theology views Christ’s sacrifice as reversing Adam’s fall. The tree causing humanity’s death becomes instrument of eternal life.

Revelation 22 describes paradise’s tree of life with healing leaves. Early Christians connected this to the cross’s transformative power.

Celtic and Eastern Orthodox variations exist, each emphasizing different theological aspects. Celtic versions stress creation’s interconnection; Orthodox emphasizes mystical union.

Eco-theology movements recently appropriated tree of life cross imagery. Environmental Christianity emphasizes creation care as faith expression.

Understanding Cross Diversity

Christian crosses number over seventy distinct types for compelling reasons. As Christianity spread globally, believers adapted religious symbols to local cultures.

Regional crosses reflect geographical context. Ethiopian, Armenian, and Celtic designs incorporate native artistic traditions while maintaining core theological meaning.

Heraldic crosses emerged from medieval chivalric culture. Military orders needed distinctive identification, creating ornate variations still recognized today.

Denominational differences produced theological emphasis variations. Catholic Church crucifixes stress suffering; Protestant empty crosses emphasize resurrection.

This symbolic diversity strengthens rather than weakens Christian unity. Each variation testifies to the Gospel’s ability to transcend cultural boundaries while maintaining essential truths about Christ’s sacrifice and salvation.

Conclusion

71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained The 71 types of Christian crosses reveal Christianity’s extraordinary cultural richness. Each variation—from the simple Latin cross to the intricate Armenian cross—proclaims the same transformative truth about salvation through Christ’s sacrifice. 71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained Understanding the history and meanings of these crosses connects modern believers to ancient apostolic traditions. These symbols aren’t mere decorations. They represent faith, martyrdom, and spiritual identity across two millennia.

71Types of Christian Croses Their History and Meanings Explained Exploring Christian crosses deepens appreciation for how the Gospel transcends borders. Whether you encounter a Celtic cross in Ireland, an Ethiopian cross in Africa, or a Jerusalem cross in the Holy Land, you’re witnessing Christianity’s universal message expressed through local artistry. The meanings explained in these 71 variations demonstrate that one execution device became humanity’s greatest symbol of hope. Every cross type testifies to redemption, resurrection, and eternal life offered through Christ’s triumphant love.